Cultivating excellence in patient care and education

A profile of Texas Family Physician of the Year, Rodney B. Young, MD

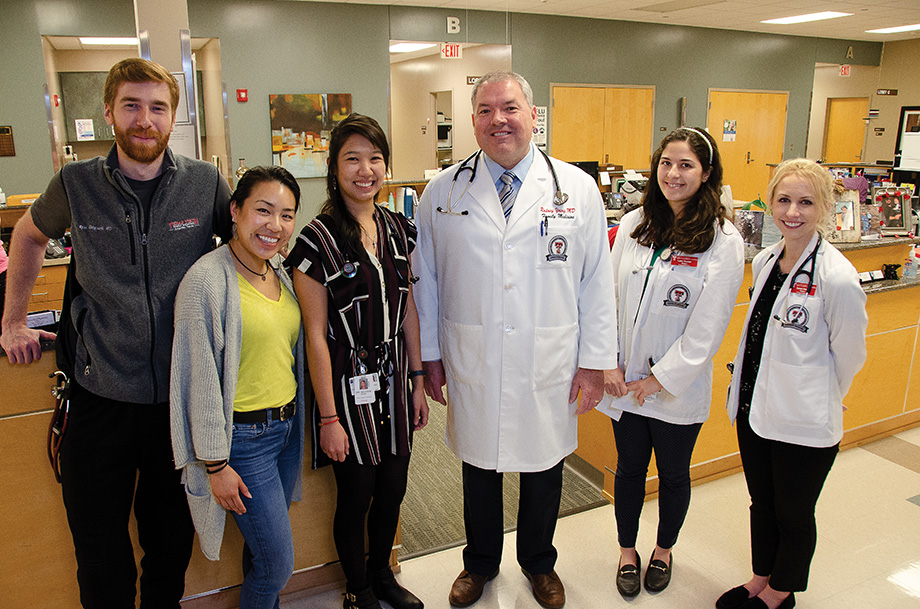

By Kate Alfano | Photos by Jonathan Nelson

Education has always played a tremendous role in the life of Rodney Young, MD, FAAFP, the 2018 TAFP Texas Family Physician of the Year. Like seeds in fertile soil, his roles as student and eventually teacher began with his salt-of-the-earth parents impressing upon him the importance of getting an education and pursuing a career where he could use his mind and not his back. It grew through his own medical education to his position as an academic family physician where he models exemplary patient care and nurtures a thriving program. It has matured further in “teaching” elected officials and policymakers the value of family medicine. And it is multiplied not only through all of the residents and medical students he has mentored, now numbering in the thousands, but also through his own two teenage daughters as they plan to pursue careers in teaching and medicine.

“If you have ever met Dr. Young, even just once, you will never forget him,” says Ronald L. Cook, DO, MBA, a Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center colleague who nominated Young for the award. “He is one of the most kind, thoughtful, wise, and genuinely sincere physicians that I have ever met. His love and excitement for all aspects of medicine — teaching, patient care, and political advancement — exudes from his personality. It is his gift and he will share it with all comers.”

Young is a natural teacher, with a warm, welcoming manner and eager ear that allows him to connect with students and patients and elevate them to a new level of knowledge and understanding. He shines in his post as professor and regional chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine at TTUHSC School of Medicine in Amarillo, splitting his time between running the department, teaching, and clinical care.

“I tell people when they ask me about my job: here’s the thing that is so wonderful,” Young told the audience at the TAFP annual awards lunch as he accepted his award. “You know that moment in the morning when you wake up and it takes you a second to figure out what day of the week it is and what’s going to happen? For me, it doesn’t matter. I am just as happy Monday morning as I am on Saturday because every day I get to do this job that has been a tremendous blessing for me. I get to interact with students, residents, faculty and friends. I see my patients and I share their lives. I am tremendously grateful for the recognition for doing what I love.”

Young started on the path to medicine early. He was born in Fresno, Calif., and raised in adjacent Clovis, in the heart of California’s Central Valley, an agricultural region in the middle of the state largely settled by farmers from the panhandle of Texas and Oklahoma looking for work in the years of the Dust Bowl. His dad ran an industrial safety equipment and fire protection company, his mom was a supervisor for the Internal Revenue Service, and his “retired” grandparents owned a ranch where they raised thoroughbred racehorses, though anyone who works with horses knows there’s a lot of work that goes into that kind of retirement, Young says.

As a young child, he recalls getting very sick with a terrible sore throat — sick enough to warrant a doctor visit at a time when such appointments only occurred when “you were knocking on death’s door.” Young took notice of how everyone treated the doctor with respect and how the doctor, in turn, was kind, caring, and knowledgeable. The doctor examined him and gave him a shot, which made him feel better within a few hours, like magic.

“It left an impression on me,” he says. “I was elementary-school age at the time but I remember thinking, ‘that’s something I could do. This doctor, people are nice to him, they appreciate what he does for them and he can really make you feel better. What could be better than that?’ It planted the seed. Going through the rest of my early years I had it in mind that being a doctor would be a good and interesting career.”

Around junior-high age, Young’s school held a career day that required him to submit his career aspiration. He entered “family practice doctor” and out popped a paragraph description he suspects came from AAFP, along the lines of “a doctor who treats the whole family and can provide for many different health care needs.” Shortly thereafter, when he was starting to think that he may be a little too big for his pediatrician’s office where he always left with a “duckie” drawn on his arm, he had to undergo a sports physical where students were herded between different stations in the cafeteria. At the final station sat a young family practice doctor who had just completed his residency and set up in Clovis. They talked briefly and the doctor gave Young his card. He held onto it and soon after that when his mom received notice in the mail that her gynecologist was retiring, Young was struck by a bolt of inspiration. Without hesitation he told his mom that the whole family could and should start seeing this young family physician and his partner, basically pitching the paragraph from AAFP. Thirty-five years later, his parents still see this now late-career physician.

“One of the biggest themes in my professional life in terms of advocacy has been what can we do to create more primary care, both in terms of the number of people who are trained to do it and the ability of the system to be accessed by everyone and at the right time.”

When it came time to choose a college, Young decided on Abilene Christian University in part for their commitment to training students for service and their highly regarded pre-medicine program but also, he says, because a friend told him the girls were pretty in Texas. He loaded up his Honda Accord hatchback and began what he didn’t know at the time would be a permanent relocation to the state — retracing the path of his Dust-Bowl-era ancestors. Following his undergraduate education he decided he would apply to a Texas medical school like most of his ACU pre-med peers. But first he took a year off to work in Houston and establish Texas residency to save on medical school tuition. While he appreciated the impressive medical complex and even had an informal offer to attend medical school in Houston, his roots were in West Texas.

“After I had visited Texas Tech, I felt so at home out there,” Young says. “Family medicine felt front and center. It really spoke to me. I remember sitting in the medical school building looking out across the street and seeing nothing but a cotton field at the time. I was thinking I don’t how many places you can get a fantastic medical education across the street from a cotton field, but this is just about my speed.”

Young met his wife, Shelly, while attending medical school and they married in his fourth year. She went to graduate school at Texas Tech, obtaining a master’s in higher education administration while he was in residency there, and she taught at a community college until they had their daughter Rachel and, later, Sophie.

His transition from residency to academia was seamless. “One of the best parts of medical education for me is that to some extent, with each step you take, you have some responsibility for teaching people who are junior to you. Even a fourth-year medical student will show the third-year medical student the ropes if they are on elective together. The same thing was true in residency. Upper-level residents were the principal hands-on teachers for interns. As you move along, that’s not only an expectation but it’s really a way for the programs to know that you’re acquiring the knowledge and skills for practice. If you can teach someone to do it, then you know what you’re doing.”

He reflected on his experiences in residency moonlighting in small-town emergency rooms and working in busier clinics, but when the opportunity arose to teach, he says it was a real “no-brainer.”

“I liked the balance. I could spend part of my time doing direct patient care and part of my time teaching other people to do a better job caring for others. It sounds a bit corny from a career academic doctor but it has always made me feel very good that my career has the potential to impact lots of people, not just my patients; different people I might share something with that they might take to their patients or teach to others. There’s an opportunity for a multiplying effect; that means something to me, that’s important.”

Though it certainly would be easy to be consumed with his administrative duties, Young has protected his time with patients — for his own well-being and to be a good chairman. “In my judgment, the best academic leaders are those who truly understand what their faculty are doing day in and day out,” he says. “I don’t think watching them do it, or completing performance evaluations, or negotiating contracts, or attending administrative meetings allows you to really understand those challenges in the same way that facing them yourself does.”

“Furthermore, too many meetings and too much administrative work can rob you of the joy of clinical practice. I didn’t go to medical school to learn how to attend meetings or fill out forms, or even to run a business. I went to learn how to take care of people, how to listen to them, how to strive to act in their best interests, and how to help them navigate our confusing health care system.”

“I do the administrative things because I hope I can help make the system better for everyone — doctors, patients, students, residents, nurses, and staff,” he says. “Those things are important, but the greatest joy of practice occurs at the bedside, in the gaze of a grateful patient who finally feels like they have found someone they can trust, someone who is listening to them and explaining things in a way they can understand, and someone who is trying to understand what they are facing. Those are the moments that really define why we joined this noble profession, and I never want to forget that or forfeit them for more meetings.”

His colleague, Evelyn Sbar, MD, associate professor of family medicine and vice-chair of TTUHSC AMA-FM, says, “Dr. Young is an amazing physician because he is an amazing person. He is witty, compassionate, smart, and perpetually optimistic. Not a day goes by that he does not bring a smile to the face of colleagues and patients. He has created a bond among our faculty team unlike anything I have ever seen — one where we each rise up and support each other, and help create our collective successes. As a friend, he is kind and gentle and always full of sage wisdom. He truly brings joy and generosity to all those with whom he interacts, influencing others to do the same.”

Young intentionally carves out time for involvement in organized medicine, primarily with TAFP and the Texas Medical Association. “Everybody’s busy, no one has time to get involved,” he says. “You just literally have to prioritize it, decide it’s important and that you’re going to do it.”

“Most of us don’t realize that virtually all medical organizations are run by the people who show up at the meetings. Literally that’s the first step. You just have to go. These are participation-based organizations. They’re trying to find out what people’s problems are, and if you take for granted that someone else is always going to be there talking about it, you miss out on the fact that your firsthand knowledge might be able to be shared in a way that speaks volumes. Your passion really conveys the importance of the message. You also miss the opportunity to bounce your ideas off of other people who might have similar concerns and together shape your argument into something that makes a lot more sense or that’s much more viable.”

“That’s my message to everyone: You need to be involved for this process to work well and you’d be surprised how easy it is to participate and to become a part of it.”

That sentiment also applies to his time advocating for the specialty at the State Capitol: he doesn’t feel he has to participate, he feels that he should. Legislators rely on “people like us” to help teach them what’s important in medicine.

When talking to lawmakers, he is a fierce supporter of boosting the primary care workforce, funding graduate medical education, making the state healthier, and removing the barriers to practicing medicine and access to care. “One of the biggest themes in my professional life in terms of advocacy has been what can we do to create more primary care,” Young says, “both in terms of the number of people who are trained to do it and the ability of the system to be accessed by everyone and at the right time.”

In turn, some of the best teachers for the medical students and residents are his patients, he says, who have become accustomed to seeing physicians-in-training in the exam room. He often asks his patients to share advice with these young people at the dawn of their careers. Their responses are often about being a good listener or being considerate of someone’s time, but not uncommonly, they are just about being “like Dr. Young.”

“It makes you feel good but it also lets the students see what an important difference a family doctor can make in someone’s life.”

He is a model of joy in medicine, enriching health care now and for the future.